Please let us now if you cannot access these papers or chapters and we will gladly email them to you.

Dyslexia is underdiagnosed!

This is the case for many reasons including poor agreement on the operational definition of dyslexia, measurement error in assessment, reliance on arbitrary cut points, and failing to assess for multiple factors in making a determination about the presence of dyslexia.

The WagnerLab has focused on clarifying prevalence rates, utilizing models that have multiple factors, and building consensus on an operational definition of dyslexia.

Publications

Kilpatrick, D.A., Joshi, R.M., & Wagner, R.K. (2019). Reading development and difficulties: Bridging the gap between research and practice. Springer Press.

Wagner, R.K., Zirps, F.A, Edwards, A.E., Wood, S.G., Joyner, R.E., Becker, B.J., Liu, G., & Beal, B. (2020). The prevalence of dyslexia: A new approach to its estimation. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 354-365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219420920377

Dyslexia is not a problem of the ears but of the eyes.

Rick Wagner and Joe Torgesen wrote a seminal paper (published in 1987) about dyslexia and the role of phonological processing which is the ability to understand and manipulate the sound structure of language. Many people have believed that dyslexia is a visual issue, but this has been shown not to be the case. And as a problem of the ears — it is not a hearing acuity issue, but rather an inability to process the sounds of words.

Publications

Wagner, R.K. (1988) Causal relations between the development of phonological processing abilities and the acquisition of reading skills: A meta-analysis. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 34(3), 261-279.

Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.192

The most common cause of dyslexia is impaired phonological processing.

A definition of developmental dyslexia that is used by the International Dyslexia Association was proposed by Lyon et al (2003):

Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result for a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge. (p. 1)

From Wagner et al (2022): Phonological processing is a signature cognitive/linguistic skill that is essential for the development of reading regardless of the script (Caravolas, 2022), and a deficit in phonological processing is regarded as a contributor to most cases of dyslexia (Hulme & Snowling, 2009; Rayner et al., 2001; Shankweiler & Crain, 1986; Share & Stanovich, 1995). The three most studied reading-related phonological processes are phonological awareness, phonological memory, and rapid naming (Wagner and Torgesen, 1987). Phonological awareness and rapid naming tend to be more related to reading than is phonological memory (Melby-Lervag et al. 2012; Kudo et al., 2015). However, phonological awareness tasks and rapid naming of digits and letters tend to be more similar to reading than are phonological memory tasks. Although there is consensus about the important role of phonological processing, whether a deficit is sufficient or even necessary for the development of dyslexia has been a point of contention.

Publications

Quinn, J.M., Spencer, M, & Wagner, R.K. (2016). Individual differences in phonological awareness and their role in learning to read. In P. Afflerbach (Ed) The Handbook of individual differences in reading: Reader, text, and context (pp. 80-92). Routledge.

Wagner, R.K., Joyner, R., Koh, P.W., Shenoy, S., Wood, S.G., Zhong, C., & Zirps, F.A. (2019). Reading-related phonological processing in English and other written languages. In D.A., Kilpatrick, R.M. Joshi, & R.K. Wagner (Eds). Reading development and difficulties: Bridging the gap between research and practice. (pp. 19-38). Springer

Wagner, R. K., Zirps, F. A., & Wood, S. G. (2022). Developmental dyslexia. In M. J. Snowling, C. Hulme, & K. Nation (Eds.), The science of reading: a handbook (2nd. Ed., pp. 416-438). Wiley Blackwell.

Mild dyslexia is remediable. Severe dyslexia is a lifelong condition.

While dyslexia may be a lifelong condition, tailored remediation strategies (such as the use of Assistive Technology), particularly when implemented effectively, early, and in proportion to severity, can empower individuals to develop reading skills and strategies and achieve success in their lives.

The Wagner Lab has as its focus understanding the causes, correlates and consequences of dyslexia. This allows for better prevention, early identification, and remediation. It also allows for better assessment and educational policy.

Publications

Quinn, J.M, & Wagner, R.K. (2018). Using meta-analytic structural equation modeling to study literacy developmental change in relations between language and literacy. Child Development, 89(6), 1956-1969. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdev.13049

Spencer, M., Wagner, R.K., Schatschneider, C., Quinn, J.M., Lopez, D., & Petscher, Y. (2014). Incorporating RTI in a hybrid model of reading disability. Learning Disability Quarterly, 37(3), 161-171. doi: 10.1177/0731948714530967

Wagner, R.K., & Lonigan, C.J. (2023). Early identification of children with dyslexia: Variables differentially predict poor reading versus unexpected poor reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 58(2), 188-202. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.480

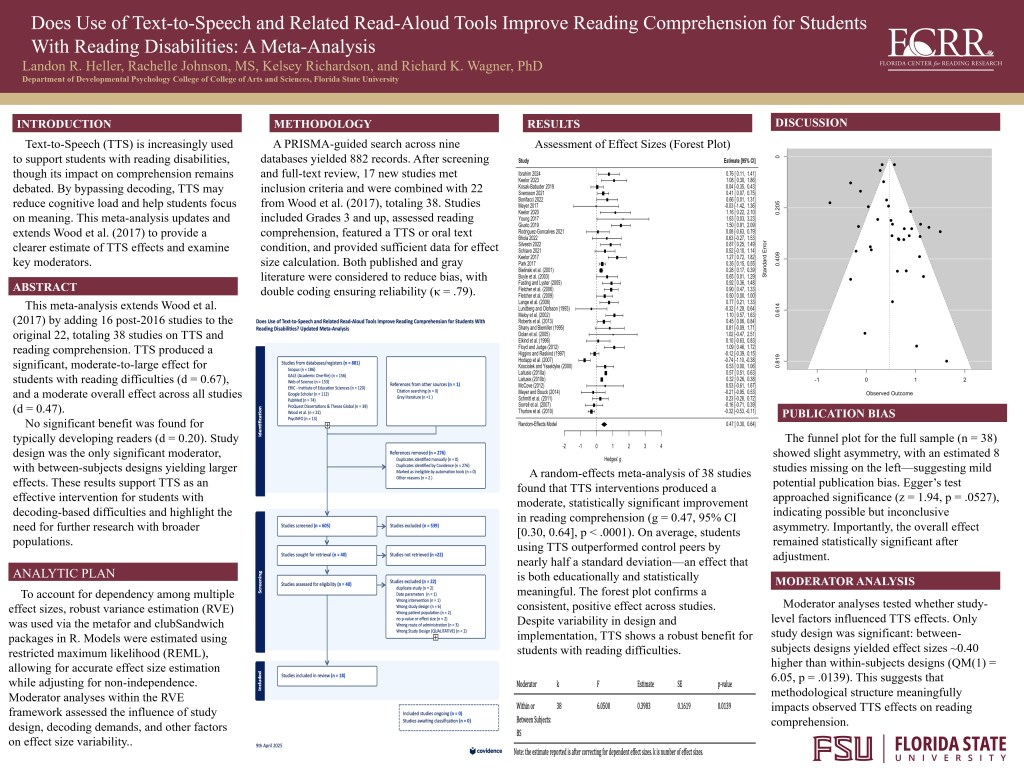

Assistive Technology can be a powerful support.

An area of research interest in the lab is the role assistive technology can play to assist students with reading disabilities such as dyslexia. Our past graduate student Sarah Wood completed a meta-analysis on the topic as well as an empirical study as her dissertation. One of our current graduate students, Landon Heller, is extending and building upon Wood’s work. Landon presented this poster for Graduate Research Day at FSU in 2025.

Publications

Wood, S.G. (2021). Comparing alternative models of reading disability by their ability to predict the compensatory effect of assistive technology on reading comprehension. https://purl.lib.fsu.edu/diginole/2021_Summer_Wood_fsu_0071E_16557

Wood, S.G., Moxley, J.H., Tighe, M.S., and Wagner, R.K. (2018). Does use of text-to-speech and related read-aloud tools improve reading comprehension for students with reading disabilities? A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities 51(1), 73-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219416688170

Prevalence varies with severity.

This makes perfect sense — the more severe the problem, the less we would expect to see it. We have tested this empirically and using meta-analysis. In addition to looking at the prevalence of dyslexia, we have done similar work on specific reading comprehension deficit.

Publications

Wagner, R.K., Beal, B., Zirps, F.A., & Spencer, M. (2021). A model-based meta-analytic examination of specific reading comprehension deficit: How prevalent is it and does the simple view of reading account for it? Annals of dyslexia, 71, 260-281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-021-00232-2

Wagner, R.K., Zirps, F.A., Edwards, A.E., Wood, S.G., Joyner, R.E., Becker, B.J., Liu, G., & Beal, B. (2020). The prevalence of dyslexia: A new approach to its estimation. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 354-365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219420920377

Having relatives with dyslexia increases the likelihood for others in the family.

The lab has had an interest in family and genetic risk for many years. Having a close relative or sibling with dyslexia greatly increases risk. Many researchers have looked at the contributions of genetic and or environmental influences on the development of reading. Rick has been studying this area for over 20 years.

Publications

Wagner, R.K. (2005). Understanding genetic and environmental influences on the development of reading: reaching for higher fruit. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(3), 317-326. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0903_7

Wagner, R. K., Edwards, A. A., Malkowski, A., Schatschneider, C., Joyner, R. E., Wood, S.,

Zirps, F. A. (2019). Combining old and new for better understanding and predicting dyslexia. ln L. S. Fuchs & D. L. Compton (Eds.), Models for Innovation: Advancing Approaches to Higher-Risk and Higher-Impact Learning Disabilities Science. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 165, 11–23.

Pure cases of dyslexia are the exception, not the rule

There is a high rate of comorbidity with dyslexia — meaning that a person often has additional learning and cognitive challenges. Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD, ADHD), learning disorders in writing and math, language disorders and anxiety are commonly found with dyslexia.

Publications

Erbeli & Wagner (2023). Advancements in identification and risk prediction of reading disabilities. Scientific Studies of Reading, 27 (1), 1-4. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/10888438.2022.2146508

Joyner, R.E., & Wagner, R.K. (2020). Co-occurrence of reading disabilities and math disabilities: A meta-analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 24(1), 14-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32051676/#:~:text=1)%3A14%2D22.-,doi%3A%2010.1080/10888438.2019.1593420

With proper accommodations, any career is open to individuals with dyslexia

Dyslexia is a learning difference not a deficit in intelligence. Supports and accommodations can make a significant difference in the classroom and the workplace. Individuals with dyslexia often have unique strengths. They may excel in visuo-spatial reasoning, problem-solving, creativity, and thinking outside the box.

Publications

Wagner, R. K. (2018). Why is it so difficult to diagnose dyslexia and how can we do it better? The Examiner, 7. Washington, DC: Interntional Dyslexia Assciation. Retrieved from https://dyslexiaida.org/why-is-it-so-difficult-to diagnose-dyslexia-and-how-can-we-do-it-better/

Wagner, R.K., Waesche, J.B., Schatschneider, C,. Maner, J.K., & Ahmed, Y. (2011). Using response to intervention for identification and classification. In P. McCardle, B. Miller, J. R. Lee, & O. J. L. Tzeng (Eds.), Dyslexia across languages: Orthography and the brain–gene–behavior link (pp. 202–213). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Dyslexia refers to a relative weakness in reading and literacy that may or may not be an absolute weakness

Publications

Quinn, J.M., Wagner, R.K., Petscher, Y., & Lopez, D. (2015). Developmental relations between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension: A latent change score modeling study. Child Development, 86(1), 159–175. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdev.12292

Quinn, J.M., & Wagner, R.K. (2013). Gender differences in reading impairment and the identification of impaired readers: results from a large-scale study of at-risk readers. Journal of learning disabilities, 48(4), 433-445. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0022219413508323#:~:text=https%3A//doi.org/10.1177/0022219413508323

A user-friendly risk calculator is in the works!

One of our prime goals in the lab is developing a risk calculator that can be easily used and understood by parents, teachers and clinicians. This calculator is based on our many years of defining and refining the constellation model of dyslexia. Much as risk calculators exist in healthcare and are helpful in understanding likelihood of disease development (breast cancer or heart problems for example), our calculator will provide a likelihood indication for dyslexia.

Publications

Schatschneider, C., Wagner, R.K., Hart, S.A., & Tighe, E.L. (2016). Using simulations to investigate the longitudinal stability of alternate schemes for classifying and identifying children with reading disabilities. Scientific Studies of Reading, 20(1), 34-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26834450/

Wagner, R.K., Moxley, J., Schatschneider, C., & Zirps, F.A. (2023). A Bayesian probabilistic framework for identification of individuals with dyslexia. Scientific Studies of Reading, 27(1), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2022.2118057